I’ve heard countless stories over the years that claim grocery store honey is fake, but I didn’t really understand what that meant. When we’re talking about pancake syrup, yeah, I get it. But honey?

What I mean is this: Most folks know that real maple syrup is the thick, mineral-rich deliciousness that’s tapped from maple trees, right? But if you check the ingredients for Mrs. Butterworth, Log Cabin, or other popular supermarket brands, you won’t see any real tree syrup at all. What you will see is high fructose corn syrup, artificial flavoring, and other grossness.

I thought maybe that was the deal with honey as well. But I’ve flipped over the bottles of supermarket brands to check their ingredients and all I’ve ever seen was “honey”. So what’s the dealio?

I finally took the time to dig in and here’s what I found out.

Also read: What’s killing our bees and how can our choices help?

Misleading labels, unknown origin, and heavy processing

The first major issue is that brands sometimes blend cheap sugar or other sweeteners into their honey in order to lower their costs and improve their profits. Then they label their product as “pure honey” without disclosing the added ingredient(s). This practice misleads consumers into buying something they may not have otherwise chosen to buy. This purposeful mislabeling is a form of “food fraud” and it’s a big problem.

A closely related problem is that many of these brands were found to have filtered out most or all of the bee pollen. Reported health benefits aside, bee pollen helps researchers to identify the botanical and geographic origin of honey. If the honey is lacking in bee pollen, the researchers can’t tell where it came from. And that’s the point.

Honey from around the world — but mostly from Asia — has been found to contain antibiotics, heavy metals (often lead), and other contaminants that we wouldn’t expect or want to find in our honey. This contaminated honey can (and does) make its way onto our store shelves. There are a few ways this can happen, but here are two oversimplified examples.

1. Accidentally mislabeling the honey

Let’s say a honey packing company in the U.S. imports their honey from Europe. To save costs, their supplier blends their higher quality honey with lower quality honey from, say, China or Indonesia. The importer believes their honey to be from one place when it is actually a blend of at least two or more origins. In this case, the packing company inadvertently mislabels its honey as pure or single-source.

2. Purposefully mislabeling the honey

Another common scenario is not so innocent. Honey brokers in the US are knowingly importing honey from China and India and then selling it to big brands. Despite countless arrests and convictions of honey smugglers around the world, the practice continues. As soon as authorities figure out how a trafficking operation works, the clever smugglers change things up and evade the investigators.

Ultra-filtered honey is fake honey

This brings up a third related issue. We now know that exporters filter out the bee pollen in order to hide the honey’s country of origin. But the process by which the pollen is removed may (or may not) be problematic.

Many believe that the only way to remove so much bee pollen is through an aggressive process called “ultrafiltration”. The high heat and pressure from ultrafiltration change the honey at the molecular level, such that the original honey is barely recognized in the final product. With ultrafiltration, we end up with a sweetener that is derived from honey, but which is no longer honey.

This is where the “fake honey” stories come from. But there are many ways to remove pollen from honey and apparently, it’s not likely to be ultrafiltration.

Adulterated honey is not “fake honey”

Vaughn Bryant, a Texas A&M professor and expert pollen investigator, is the researcher whose 2011 study commissioned by Food Safety News (FSN) spurred most of the fake honey stories we see today. A more recent 2018 study by Australian scientists continued the conversation when it found that as much as 20% of (non-local) honey found in Australian markets had been adulterated.

Neither Bryant nor the Aussie scientists called the honey “fake”. The FSN writer (indirectly) did in 2012 and journalists ran with it, using “fake honey” in their clickbait titles. Years later, the journalists who covered the 2018 Australian study did the same.

Bryant followed up in 2012 by saying that while the filtering of pollen is problematic in that we can’t otherwise determine its nectar or geographic origin, the honey is likely highly filtered, but not ultrafiltered. Bryant also agreed with the National Honey Board that “honey is made by honeybees from the nectar of flowers and plants, not pollen.” And “honey is still honey, even without pollen.”

So while it is true that ultra-filtered “honey” is no longer honey, highly filtered honey is still honey… with or without its pollen.

Filtered honey isn’t always fraudulent

When honey is gathered from the hive, the harvest inevitably includes large bits of beeswax. No matter how careful the harvest, small bits of bee wings and legs can also make their way into the honey. (Bothersome, I know.)

Large commercial brands will highly filter the honey to remove all these large and small particles. The result is an exceptionally clear look that makes the honey more attractive on store shelves. Filtration also smooths out the texture, making it easier to squeeze from those bear-shaped (and other less silly-looking) plastic bottles. This filtration also helps the honey to not crystallize so easily.

Unfortunately, this heavy filtering can also remove even smaller particles of pollen, as well as its propolis. While raw foodists, “beegans”, and other healthy eaters (myself included) might sarcastically call this practice “criminal”, this case of pollen removal isn’t fraudulent.

Oh, and by the way, this crystal layer of glucose that forms at the top of the honey jar is mostly a problem for U.S. consumers. In other countries, crystallization is recognized as something that happens naturally. They just warm the jar a little and stir the crystalized glucose back into the honey. No biggie. (Personally, I love to scrape it off the top and eat it. Nom nom!!)

Buy honey labeled as raw, unfiltered, local, and/or organic

With all this fake honey hoo-ha abound, how can you find truly pure honey? As we’ve learned, the adulteration of honey happens — sometimes deliberately and sometimes inadvertently. Either way, the words “pure honey” on the front side of the label are not enough to go by. And since additives aren’t always disclosed, checking the ingredients on the back of the label is also not a guarantee of what’s inside.

While the labels can be tricky, there are a few claims that tend to hold up.

Organic honey

Conventional honey is often filtered through a natural, sedimentary rock called diatomaceous earth. While diatomaceous earth is absolutely loved by healthy and eco-lifestylists as a natural alternative for everything from flea control to detoxification, it’s actually a no-no when it comes to the organic certification of honey. High-pressure filtering and any fine mesh filters are also prohibited for organic honey.

These restrictions on fine-filtering mean the bee pollen stays put in organic honey. As a result, consumers reap the added health benefits from the pollen and the honey remains traceable.

Local honey

The term “local” doesn’t come with any enforceable requirements, as an organic certification would. However, Vaughn Bryant (the pollen investigator mentioned earlier) says that in all his many years of analyzing honey, he has found that “locally-produced honey is usually full of pollen and is most often authentic in terms of what it claims to be.”

Raw honey

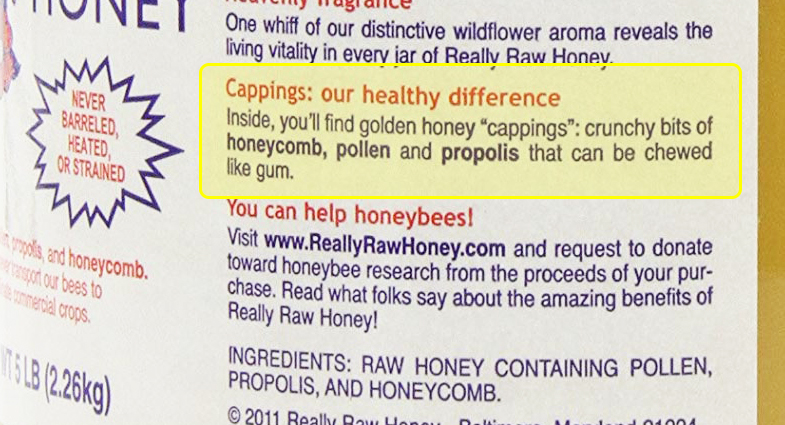

Raw honey is closest to how the honey would exist naturally in the beehive. It is harvested by extraction, settling, or straining. Some raw honey is minimally heated, just enough to get the honey into the jar and never above 118-degrees, which is the temperature that kills the healthy enzymes we want. It may also be minimally filtered to remove the larger bits of honeycomb or wax, but the pollen and propolis remain intact.

Really Raw Honey (Sustainably Harvested)

Good to know

Raw, local, and organic honey is most likely to have the pollen that you would expect it to. Even without its pollen, honey offers a slew of benefits from antibiotic wound-healing properties to soothing sore throats. All this said, it is important to note that honey is not considered a “health food” and it should also never be fed to infants under one year of age.

Honey is not a “health food”

While honey is certainly healthier than white sugar, corn syrup, and other non-natural (refined) sweeteners, it is still a sugar and is not considered a “health food”.

Honey does contain trace amounts of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, enzymes, and other nutrients. But it is also high in fructose and glucose, which makes it high in calories and carbohydrates. Like refined sugars, honey (and most other natural sweeteners) can still contribute to weight gain and other unhealthy conditions. As such, it should be used sparingly.

Honey should never be fed to infants

Honey may contain Clostridium botulinum spores that can cause “infant botulism” in babies under one year of age. While we are all routinely exposed to these spores in dust and soil, our gastrointestinal tract has developed enough after our first 12 months of life that we are not typically affected. However, infants need time to build their gut walls and the beneficial bacteria that help to combat these spores.

Infant botulism is rare but serious. While most cases have actually been traced back to dust (not honey), it is still considered unsafe to feed honey to infants under 1 year of age. This said, honey is considered safe for moms to consume during lactation, as the spores are not transmitted in breast milk.

[accordions] [accordion title=”Research” load=”hide”]

- https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/UCM595961.pdf

- https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/hsi-chicago-seizes-nearly-60-tons-honey-illegally-imported-china-0

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-32764-w

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2011/11/tests-show-most-store-honey-isnt-honey/

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2011/11/top-pollen-detective-finds-honey-a-sticky-business/

- https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2011/08/honey-laundering/

- https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/honey-gate-how-europe-is-being-flooded-with-fake-honey/

- https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2011/11/25/142659547/relax-folks-it-really-is-honey-after-all

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7M8R4350iw

- https://www.nbcnews.com/business/consumer/honey-its-only-pure-if-theres-no-added-sugar-or-n74951

- https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm337628.htm

- https://www.honey.com/faq

- https://www.fda.gov/downloads/food/guidance%20complianceregulatoryinformation/%20guidancedocuments/foodlabelingnutrition/foodlabelingguide/ucm265446.pdf

- https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/1994/05/enforcement-policy-statement-food-advertising

- https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/advertising-faqs-guide-small-business

- https://www.losangelescountybeekeepers.com/blog/2012/4/23/theres-more-to-the-highly-filtered-honey-story.html

- https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Rec%20Apiculture%20Standards.pdf

- http://www.infantbotulism.org/general/faq.php

[/accordion][/accordions]