Many of us, who are already on the path to eating healthier, are also on a path to eating more humanely. Incidentally, those two goals tend to go hand-in-hand, which is nice.

Our journey might lead us to reduce or eliminate our consumption of meat, dairy, and eggs. Or we may choose products from sustainably and ethically raised animals. In this case, we’ll look for labels such as “pasture-raised”, “certified humane”, or “MSC certified” to filter out the stuff we don’t want from the stuff that we do.

This is helpful when it comes to choosing animal products from cows, pigs, chickens, and fish. But what about the bees? How do we choose healthier and more ethical honey?

In this article

- No judgment here

- The issues with most commercial honey

- Sustainable & ethical honey

- Questions you can ask farmers about their sustainable and ethical beekeeping practices

No judgment here

Before we dive into what makes honey ethical, I’d like to mention that my goal is not to enter the debate around whether we should avoid honey (or other animal products) altogether. As a no-leather wearing vegetarian who feels constant guilt over not eating a fully vegan diet, I do feel that eliminating the consumption of animal products entirely is a worthy goal.

That said, I’m not here to convince anyone to change their diet or lifestyle. My goal is simply to help those, like myself, who will consume honey, to make better choices.

It started because I love honey and I believe in both its health and holistic healing benefits. At the same time, I’m aware of our growing bee problems with regards to sustainability. And, in researching the ways we can minimize our impact and even contribute to the solution, I’ve also learned of the cruelty that often accompanies commercial beekeeping.

As I’ve alluded to earlier, animals raised in a more natural and cruelty-free environment also make for healthier products. With that in mind, non-vegans seeking healthier and/or more cruelty-free options can find them by avoiding products derived from factory-farmed animals, including factory-farmed bees.

Instead, choose products where the animals or bees have been allowed to:

- eat the diets intended by nature

- exercise their natural instincts and behaviors in a healthy, free-roaming environment

- live as closely as possible to how they would in the wild

The issues with most commercial honey

If you’re surprised to see the phrase “factory farm” associated with bees, don’t be. Conventional beekeepers often disregard what’s best for the bees in an effort to maximize the colony’s honey output at the lowest possible cost. As a result, the conditions in most commercial bee farms (apiaries) are just as cramped, unhealthy, and inhumane as your typical factory farm.

Here are three really important examples of what should never happen to our bees.

1. Busy bees: overworked and under-compensated

Bees are naturally hard-working, highly productive insects. Unfortunately, greedy honey producers can trick bees into working even harder. They do this by housing them in hives that are much larger than the colony needs.

The already busy bees will put in some serious overtime to fill the extra space with as much honey as they can before winter, either to ensure they have stored enough food or perhaps to better insulate their oversized hive. Either way, the bees can literally work themselves to death in an effort to provide the rest of their colony with the best chance for survival.

Harvesting the honey

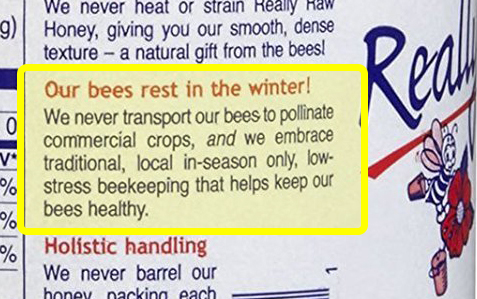

By the time autumn arrives, a healthy hive should have enough honey in-store to feed the colony through the cold months. More practically-minded beekeepers in the 1800s would wait until spring to harvest any excess honey that the bees didn’t need the prior winter. But today’s industrial honey producers extract most or all of the hive’s honey during the autumn peak, just when bees need it most. (By the way, beekeepers in the 1800s didn’t supersize the hives either.)

To make matters worse, today’s greed-keepers replace that honey with sugar water or high fructose corn syrup, both of which lack the nutrients bees need to thrive. Suffering from malnutrition and colder conditions, a high percentage of the bees don’t survive winter. Their immunity is also compromised, leaving the survivors more susceptible to the various parasites and pathogens that like to infiltrate beehives during warmer months.

Really Raw Honey (Sustainably Harvested)

2. Weary travelers

In addition to exploiting bees for their honey, commercial beekeepers often earn a second income by renting their bee colonies to large-scale farms.

The bees can travel cross country, several days at a time in 18-wheelers during the hot summer months, in order to pollinate the farms and groves that produce our almonds, avocados, and other supermarket produce. Not only is this long-distance travel highly stressful for the bees, but they are fed the same nutritionless sweeteners during the trip as they are fed during the cold, winter months.

These traveling bees do get to forage naturally once they reach their destination, as this activity pollinates our agriculture. In order to get the diverse mix of nutrients that their bodies need to stay healthy, bees must gather nectar from a diverse mix of flowering plants. But most of the farms that rent their pollination services are single (mono) crop environments that lack this diversity. Again, this malnutrition weakens their immune system, making the bees susceptible to pests and disease.

Also, when the farms employ conventional farming methods (instead of organic or biodynamic farming methods), the bees bring the pesticides and other chemical farming inputs back to the colony by way of the nectar they’ve gathered. These toxins are inadvertently fed to the drones, the queen, the young brood (bee larvae)… and to us, once we eat their honey.

3. Getting in the queen’s way

The queen bee will lay up to 1000 eggs per day for the duration of her 2- to 5-year life. Once she dies or becomes less productive, the worker bees will produce another queen. Only a few days old, the new virgin queen will leave the hive to mate in-flight with as many as 20 drones. This natural process ensures the survival of the fittest, as only the strongest, fastest drones can catch and mate with the queen. As such, only the strongest genes are passed to the next generation.

After this initial flight, the new queen bee never leaves the hive again… unless the bees outgrow their hive and decide they need to divide themselves into two separate colonies. When her majesty does leave the hive for this purpose, she takes about 50% to 60% of her worker bees with her. Depending on the colony, that could mean anywhere from a few thousand to tens of thousands of bees leaving the original hive.

Often times, the bees will swarm to a nearby tree for some time, as they scout for a suitable new location to call home. Folks can really freak out at the site of a huge bee swarm, but it’s an entirely natural process that is critical for sustainably growing the bee population.

Sorry! No natural breeding, no natural swarming.

Unfortunately, commercial beekeepers interfere with the queen’s duties with regards to both breeding and swarming.

First, the beekeepers will suppress natural swarming by clipping the queen’s wings and thereby preventing her from leaving the hive to start a new colony. They’ll also artificially inseminate her in a particularly cruel way* and harvest her eggs. This forced breeding allows beekeepers to create multiple queens and expand their colonies as quickly and as often as they wish. (* Bees are sentient beings, meaning they do have a central nervous system and they do feel pain.)

While this sounds like a practical way to combat dwindling bee populations, the unnatural process weakens the gene pool, making the new generation more susceptible to pathogens and parasites. And since the process is repeated over and over, it also puts future bee generations at immense risk by eliminating the natural gene selection that ensures the survival of the fittest.

Bees are sentient beings, meaning they do have a central nervous system and they do feel pain.

Sustainable & ethical honey

Many of my vegan friends will say there is no such thing as ethical honey. After reading several blogs on biodynamic beekeeping that follow methods outlined last century by Rudolf Steiner, I’m not sure I agree.

But to their point, most honey producers are not practicing ethical, biodynamic beekeeping. Plus, the overall demand for honey far outweighs our supply, so any effort to reduce consumption is definitely a good idea.

And if you do want to continue eating honey (as I do), how can you ensure it’s ethical? Or at least ‘more’ ethical than commercial honey?

- One way is to buy honey from a small, local farm, ideally by visiting the farm yourself. This way, you can see everything firsthand and ask questions about their practices.

- If visiting the farm isn’t possible, you might try your local farmer’s market. While you won’t be able to see their practices for yourself, you can still ask questions and engage in a thoughtful conversation with the farmer.

- Many smaller — and sometimes even the larger — grocery stores also carry local, family-farmed honey. While there is no guarantee, the practices of these smaller, family-run farms have a far higher tendency to be more ethical and sustainable than large commercial operations.

- Finally, if local honey is not an option, you can always jump online and buy honey that is labeled as raw, unfiltered, organic, or biodynamic. Again, while these characteristics are no guarantee of ethical beekeeping, their related farming practices are likely to be more sustainable, which is inherently better for the bees. They are also more likely to follow more balanced beekeeping methods.

Overall, ethical honey would come from beekeepers that are more concerned about the health and welfare of the bees than for maximizing their honey output. This is a big ask for anyone trying to make a living as a beekeeper, but these folks do exist.

Questions you can ask farmers about their sustainable and ethical beekeeping practices

What are some of the sustainable practices that often lead to more ethical beekeeping? You might find the below list helpful if you have the opportunity to speak with your local beekeeper.

Or if you plan to buy your honey online and can’t find the answers you need on their website, you can ask via their contact-us page or via whatever email or phone number they provide.

Engaging in natural instincts

- Do you allow your bees to produce their own queens and brood naturally vs. by artificial means?

- Do you allow your bees to engage in natural swarming practices to expand their colonies? (And do you clip the queen’s wings?)

- Do you create pre-made honeycombs (called “foundation sheets”)? Or do you allow your bees to build their own to suit their colony’s custom needs?

- Do your bees forage from an organic or otherwise chemical-free farm with a variety of flowering plants?

- Is there a variety of plants (biodiversity) for the bees to forage?

Overall, ethical honey would come from beekeepers that are more concerned about the health and welfare of the bees than for maximizing their honey output.

Care & treatment

- How do you treat your hives for parasites? (Ideally, they use organic substances such as formic acid or oxalic acid, in place of pesticides.)

- Do you treat your bees with antibiotics? (Ideally, their practices strive to create healthy colonies that can more naturally protect themselves from illness. Honey and propolis are, after all, naturally antiseptic.)

- Are your hives made from plastic? Or do you use more natural materials, such as wood, straw or clay?

- Do you rent out your bees for commercial pollination services?

Harvesting the honey

- Do you harvest honey in the fall, when hives are at their fullest (and when bees need their honey most)? Or do you wait to harvest the excess until spring, so the bees are more equipped to survive the winter?

- When you harvest the honey, do you replace any of it with sugar, corn syrup, or other substitutes?

- Do you save any honey in order to supplement your hives in emergency situations, when bees don’t have enough to get them through the winter?

Wow, so many questions! It’s a lot to think about, I know. Still, with this list, you should be able to show your beekeeper that you know your stuff and hopefully you can get the answers you need to make an informed decision. Also if the beekeeper truly does care about treating their bees well, I would think they’ll not only be open to your questions — but will welcome them.

Really Raw Honey (Sustainably Harvested)

A note on bee pollen

Beyond honey, bee pollen is also harvested from the hive and sold as a superfood or supplement. Pollen is an important food source for the colony, particularly for the young, developing brood. Instead of buying bee pollen directly, consider getting it from the honey. While most commercial honey lacks pollen, honey labeled as raw and unfiltered will naturally contain bee pollen, as well as the also highly sought after propolis.

- Research

- https://beeinformed.org/results/honey-bee-colony-losses-2017-2018-preliminary-results/

- http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/current/BeeColonies/BeeColonies-08-01-2018.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/colony-collapse-disorder

- https://www.petakids.com/food/honey/

- https://grist.org/food/when-i-eat-honey-do-i-hurt-bees/

- https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/01/27/581007165/honeybees-help-farmers-but-they-dont-help-the-environment

- http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20140502-what-if-bees-went-extinct

- http://www.theabk.com.au/articles/2016/8/3/is-beekeeping-sustainable

- https://thehoneybeeconservancy.org/pollinators/

- https://thehoneybeeconservancy.org/2017/12/09/bee-hotels/

- https://thehoneybeeconservancy.org/why-bees/mason-bees/

- http://bees.caes.uga.edu/bees-beekeeping-pollination/getting-started-topics/getting-started-honey-bee-management.html

- http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150615-the-truth-about-bees

- https://abcnews.go.com/US/growing-california-almonds-takes-half-us-honeybees/story?id=52265334

- https://www.peta.org/issues/animals-used-for-food/animals-used-food-factsheets/honey-factory-farmed-bees/

- https://www.apidologie.org/articles/apido/abs/2005/04/M4095/M4095.html

- https://www.bachbiodynamics.com/uploads/1/6/3/6/16367710/biodynamic_beekeeping_essay.pdf

- https://entomologytoday.org/2016/08/24/traveling-bees-have-more-stress-and-shorter-lives/

- http://blogs.evergreen.edu/terroir-zack/life-cycle-of-the-honey-bee/

- https://www.perfectbee.com/learn-about-bees/the-life-of-bees/how-and-why-bees-swarm

- https://friendsoftheearth.uk/bees/bee-cause-what-you-can-do

FREE DOWNLOAD

Natural Living Guide

Find practical tips & natural alternatives to the everyday chemicals that invade our lives.